Advertising single malt whisky (1950s to 1980s)

The revival of interest in single malt Scotch whisky in the UK in the late 1950s and early 1960s happened with virtually no advertising or promotional spend from the distillers. Demand grew largely by word of mouth – primarily from well-educated and often affluent whisky drinkers looking for what they considered to be more "authentic" and traditional Scotches, in an era when blends ruled the roost and there was a growing fashion for lighter and (according to critics) less flavoursome whisky.

The first single malt advertising campaigns were aimed at these converts and at curious connoisseurs, willing to seek out and pay premium prices for a type of whisky that was said to be richer in character and more prestigious than "ordinary" mass-marketed blends. The adverts emphasised the importance of the process of pot still distillation; the time-honoured skills of the men who worked the stills and turned the malt, and the wider range of rich flavours that were to be discovered in single malt.

But they also played up to the little-known myths, legends and drinking rituals that the brotherhood of malt aficionados believed set them apart from the average whisky drinker.

One of those oft-stated beliefs was that single malts should be enjoyed unadulterated: that they should only be consumed "straight" in order to fully appreciate their subtle flavours. Journalists such as Robert Bruce-Lockhart trotted out the hoary old cliché that “there are only two things a Highlander likes naked, and one of them is a single malt.” Other (usually elderly and male) traditionalists fulminated against those who had the temerity to add soda, lemonade or ginger ale to their dram. God forbid that anyone should follow the American custom of drinking whisky “on the rocks” (ice was said to deaden the taste buds) and the most extreme puritans cavilled even at the addition of a few drops of water!

The “superiority” of single malts over blends was frequently implied and was often overtly stated in adverts. Cardhu, for example, was “considerably richer in flavour” than “usual whiskies”. William Grant’s asserted that “unlike blended whisky, Glenfiddich has a full-blooded smoothness all of its own”. It was understood that it took a true connoisseur to recognise the difference and the adverts played to the vanity of the reader, cajoling him (yes, the adverts were almost exclusively aimed at men) to join the happy and select band of whisky experts who had discovered the “real stuff” of whisky history. Another Glenfiddich advert spoke directly to those well-informed drinkers who wished to move on from premium blends and “trade up”, with the invitation “Now that you know your Scotch, taste what came before”.

The claim to superiority was to be delivered in its most extreme (and tongue-in-cheek!) form in the mid-1980s, when Glenmorangie’s US distributor commissioned the controversial “Darwin was Right” advert. It portrayed the brand at the front of the whisky evolutionary chain, ahead of the big-selling premium blends Dewar’s, Johnnie Walker and Chivas Regal.

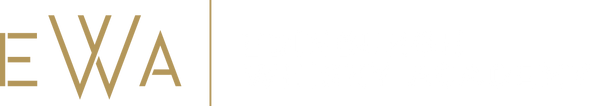

The privilege of drinking single malts came at a price, as they sold for as much if not more than the premium and deluxe blends of the day. Well-versed in the marketing of luxury products, however, the adverts were unapologetic. The consumer was reminded that it was more expensive to produce a single malt, and that it was worth paying a little more for the greater craftsmanship and more expensive ingredients required to create such a distinctive, rich and full-bodied spirit. They suggested that a true connoisseur would appreciate that the experience of drinking a single malt was worth the extra cost. Aberlour spoke for many when it proclaimed that “Once you taste it, you can afford it”.

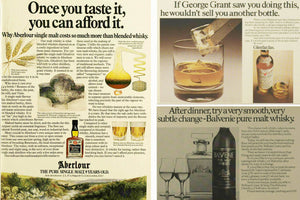

During the 1970s, advertisers sought to increase sales by wooing other premium spirits drinkers. One tactic was to promote single malts as alternatives to fine cognacs, to be “sipped and savoured” after dinner. These adverts certainly succeeded in providing a further point of difference between malts and the lighter blended Scotches, and the emphasis on their enjoyment as digestifs helped establish them in the minds of the cognoscenti alongside the most prestigious of cognacs. However, the success of this positioning was subsequently seen as a significant barrier to expansion – it created a popular perception that single malts (as opposed to blends and other spirits) might not be an appropriate choice for drinking on other occasions.

Today, single malts are advertised as special flavouring ingredients in cocktails; in rich cooking sauces, and to be enjoyed with mixers. One leading Islay brand is promoted for drinking in a Smoky Cokey, mixed with cola! Such sacrilegious suggestions would have been unthinkable even so recently as the 1990s. But the marketing of single malts has evolved greatly since the early days of the revival.

The early success of advertisers in presenting single malts as intrinsically more prestigious and superior to blends alarmed the sales teams at many leading whisky companies, where blends remained the corporate bread and butter and accounted for up to 98 per cent of sales volumes. Several firms attempted to moderate that impression in the 1970s – while sprinkling some single malt fairy dust on their blends – by advertising their singles as part of their core range of Scotches.

This tactic was widely adopted by companies such as Bell’s, The Glenlivet Distillers and Macdonald & Muir. Distillers Company Limited (DCL) partnered Cardhu prominently in its adverts for Johnnie Walker. Significantly, Johnnie Walker has maintained that “portfolio” approach into the 2020s: the brand is supported, for example, by the “four corners” distilleries – Glenkinchie, Caol Ila, Cardhu and Clynelish – which are “crucial to the art of whisky blending at the heart of Johnnie Walker”. Their visitor centres have been redeveloped as much to educate visitors about the Johnnie Walker brand as they are to promote the single malts themselves.

As the 1970s came to an end, another concern arose about the advertising of single malts. Success had been built around marketing the product as a more “authentic” product than blends, with a reverential tone that some younger and more irreverent drinkers considered to be pretentious and veering too far in the direction of po-faced elitism. It would be an exaggeration to claim that the spirit of punk rock was at play, but the first signs of a more genteel rebellion emerged. Hugh Mitcalfe, marketing director at Glen Grant, was one of the first to prick the bubble, recruiting the Punch humourist Miles Kington and the illustrator Michael ffolkes to create the “Chairman’s Hairy Knees” campaign at Glen Grant. The irreverent campaign took humorous aim at the “kilts ‘n’ heather” approach to whisky advertising, appealing to non-traditionalists who wanted to drink single malts but not to be identified with the fuddy-duddy tendency of single maltery.

This trend was to grow rapidly in the 1980s, as many single malts outgrew the traditional imagery and fact-heavy copywriting of the 1960s and 1970s, and embraced humour and quirkiness. Hugh Mitcalfe moved to Macallan in 1978, for example, and hired the advertising executives David Holmes and Nick Salaman to launch the long-running and hugely-successful “The Macallan. The Malt” campaign which introduced the world to such tall stories as the Tale of the Luggy Bunnet and “Nae Macallan. Nae Fish".

The Scotch Malt Whisky Society (SMWS), founded in 1983, introduced what was virtually a new language for tasting notes and an influential new approach to promoting single malts, and Laphroaig and Ardbeg were among the brands to go down the irreverence road in the 1990s.

By 1980, single malts still accounted for only around 2% of sales of Scotch whisky. The category was extremely profitable, however, and in many of the greatest Scotch whisky markets – in the USA and UK, especially – clever advertising and promotion had resulted in malts gaining proportionately far greater media coverage than blends. Their success posed serious questions for leading companies such as DCL (United Distillers from 1987) and Chivas Brothers, about how to exploit the popularity of single malts without seriously damaging sales of their blends. It was a challenge which led to a great deal of internal debate and turmoil within sales and marketing teams over the following 20 years.