A History of Glenlivet (the place)

In this post, whisky writer Iain Russell explores the rich record of this sparsely populated glen which has, over the years, contributed so much to the broader story of Scotch. From the well-known smuggling days to its distinct brand and style of whisky, Iain reveals the facts and revels in the tales of the colourful characters who resided in the area, many of whom went on to found some of the country's leading distilleries and brands.

Glenlivet is one of the most famous names in Scotch whisky.

Today, it is associated primarily with one great distillery and brand. However, this secluded glen (or valley) in rural Banffshire was once the home of hundreds of small distilleries and it has had an influence on the course of Scotch whisky history that is quite disproportionate to its size and population.

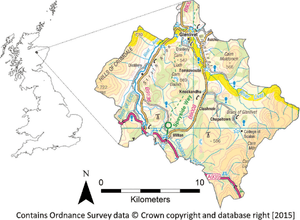

The River Livet is formed high in the Ladder Hills, foothill s of the Grampian Mountains, in an area known as the Braes of Glenlivet. It flows for nearly nine miles north through the glen to which it gives its name, past the gentler slopes of lower Glenlivet, and joins the River Avon (a tributary of the Spey) near Bridgend.

The name, derived from the Gaelic liobh ait (roughly translated as the smooth or flowing one) is generally pronounced ‘livit’ today, but it was traditionally pronounced ‘leevit’ by the Gaelic-speaking inhabitants. Until the mid-19th century, when spelling conventions became more firmly adhered to, it was often spelled Glenlivat.

A map of Glenlivet.

Glenlivet’s first road was built in the 1820s, connecting Bridgend in the north with the village of Tomintoul in Strathavon but by-passing the great natural bowl of the Braes. Even with the road, it was often challenging to reach and to travel through Glenlivet, especially in winter when the snow fell for longer and lay deeper than in surrounding glens. The remoteness of the area, and of the Braes in particular, was one reason for its emergence as a famous centre of whisky production.

Glenlivet, from the summit of Benrinnes.

The Glenlivet Distillery is bathed in sunlight, right foreground. Image courtesy of Chivas Brothers Archive.

William Gordon of Bogfoutain is the earliest known distiller in the glen. It was recorded in 1790 that he ‘acquired a considerable fortune, chiefly by his industry as a tenant and by distilling and retail of whisky’ at his farm at Auchorachan.

Commentators remembered later that distilling became a major cottage industry in Glenlivet soon afterwards, at the beginning of the long wars with Revolutionary France.

A steep rise in duties on wines and spirits drove up prices, making illicit whisky-making a profitable business for those willing to defy the law.

Although there were only around 2,000 people living in Glenlivet by the 1820s, there were said to be over 100 small stills at work there. None had a permit to do so legally.

Copper stills (small and light enough to be carried manually to and from their hiding places) were purchased in the market town of Keith, and they were often worked by women of the house, using the ale they brewed from the local crop of a four-row barley, known as bere.

One old smuggler said later that ‘I suppose there were not three people in Glenlivet in those days who were not engaged directly or indirectly in the trade.’

Because of the difficulties in accessing the glen, the Excise authorities were unable to mount surprise raids to search for and destroy the illicit stills. Gangs of smugglers – ‘Glenliveters’ - bought and carried the whisky south, usually in pairs of small 10-gallon casks called ankers which were slung across the backs of sturdy ponies.

Smuggled ‘Glenlivet’ became very popular in Scotland’s towns and cities and fetched higher prices than the products of licensed Lowland distilleries, which were often criticised for their harsh flavours and for the severe head- and stomach-aches suffered after drinking them.

Smugglers claimed that an anker of Glenlivet could fetch at least £1 more than one of another make.

A leading distillery owner, John Stein told a government inquiry in 1822 that "I believe that there are some people in the higher stations of life who prefer the Glenlevit whiskey [sic], and who would almost pay any price for it... There is only a limited quantity of it to be got, and those who can afford to purchase it will pay almost any price, rather than not have it." In modern parlance, ‘Glenlivet’ had become a premium product!

Workers at the Glenlivet Distillery, 1924.

The smugglers also bought illicit whisky from ‘sma’ stills’ in the Cabrach, Glen Nochty and other remote areas of Banffshire.

When the quality of the whisky and the romance of the story of Glenlivet whisky captured the imagination of the public, they advertised this whisky, too, under the title.

‘Glenlivet’ became the popular generic name for the pot still ‘style’ of the whiskies made in and around the Spey valley, just as ‘Cheddar’ came to be the name given to a popular style of cheese, and ‘London’ to a style of gin.

It was eulogised by the famous novelist Sir Walter Scott, who made sure that ‘Glenlivet’ – which must surely have been obtained from illicit sources - was served at functions during the great ceremonial visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822: “the king drank nothing else”.

There are no contemporary tasting notes in the modern sense to provide us with a sense of what this smuggled Glenlivet was like.

However, Elizabeth Grant of Rothiemurchus described the whisky she provided from her cellar for the Royal functions in 1822 as ‘mild as milk’, having been stored ‘long in wood and long in uncorked bottles.’ It had, she wrote, the true ‘contraband’ flavour.

This ‘soft’ and mild character was attributed it to the fact that the whisky makers in Glenlivet and other remote glens were able to run their stills ‘lazily’ over a small fire.

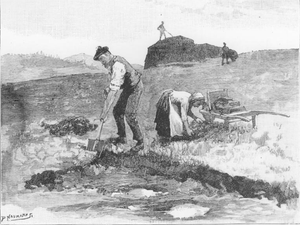

‘The real Glenlivet’, as it was known, was made from malted barley or bere alone, while Lowland distillers might add wheat, rye or other unmalted grain to their mashes. And it was characterised by a strong ‘peat reek’: the glen’s inhabitants relied almost exclusively on peat for drying their malt, as they did for heating and cooking.

In contrast, the leading licensed distillers of the Lowlands used shallow stills and ran them rapidly because Excise duty was charged on still capacity. This practice was believed to ‘scorch’ the wash, contributing to the harsh flavours found in the final product. More importantly, prolonged contact with copper is known to have a beneficial effect on distillate – it results in the removal of volatile sulphur compounds and the development of esters which provide a fruity character.

Smuggled whisky, made in a traditional small copper still and run slowly, may have received more copper contact than one run through a shallow still at great speed. It was certainly believed to have a milder flavour than Lowland whisky, which was often described as being pungent and noxious. Encouraged by the popular demand for their whisky, the Highland whisky smugglers became increasingly bold. There were reports of large bands travelling to the outskirts of Scotland’s towns and cities to sell their casks and fighting with Excisemen who tried to intercept them.

Glenlivet’s landowner, the Duke of Gordon, had benefited from a trade which earned ready cash for his tenants with which to pay their rents.

Initially, he turned a blind eye to the illicit trade. But there was growing condemnation of the lawlessness on his estates, where his tenants had become ‘daring, profligate and full of insubordination.’ He was forced to act.

The Duke announced that tenants found distilling illegally would be prosecuted to the full extent of the Excise laws and, if convicted, evicted from their homes.

Meanwhile, the Excise Act of 1823 had made it easier for small distilleries to operate legally in the Highlands. He encouraged his tenants to take out licences to distil legally.

George Smith, a farmer at Upper Drumin and a grandson of William Gordon of Bogfoutain, became one of many new ‘entered’ distillers, as those who became legal were known. The majority lived in the Braes, formerly the hotbed of illicit distilling in the area. Joining Smith at the northern end of the glen, however, was Captain William Grant, who revived distilling at Auchorachan after acquiring equipment from a failed distillery in the Braes.

Those who chose to continue distilling illegally were hostile to the new enterprises, as they knew that licensed distilleries would bring a permanent Excise presence to the glen.

Smith mounted an armed guard at his premises, after he received threats to burn them down, and was frequently threatened with violence on his trips to markets. At his request, however, soldiers were deployed in the area to support the Excise officers and the trade in illicit Glenlivet was all but stamped out by the early 1830s.The small, newly-licensed distilleries in Glenlivet found it difficult to compete with the illicit distillers and the larger established distilleries in the south of Scotland, and most were forced to close within a decade. George Smith, who was effectively bankrupt in 1826, would have gone the same way. However, the Duke of Gordon realised how important his business had become to the local economy, as an employer and as a regular and reliable customer for the bere grown on the estate.

Digging peats in Glenlivet, 1890. Image courtesy of Chivas Brothers Archive.

The Duke provided Smith with loans and helped him find customers to enable him to carry on with (literally) his seal of approval – a later announcement published in several London newspapers stated that ‘By His Grace's permission, the Ducal arms, on the seal and label, will distinguish the Real Glenlivet from all others.’

And the distillery did indeed provide an important source of revenue when times were hard – the estate’s factor told the Duke in 1828 that “the tenants have hardly any other means at present of turning their crop into cash but from the part of their bear [sic] which is consumed by the distillery we got carried on...".

George Smith became the sole licensed distiller in the glen after Auchorachan closed in 1854. His business expanded, and in 1859 he relocated his Glenlivet Distillery from the hillside at Upper Drumin to his farm nearby at Minmore. Output increased to 93,000 gallons per annum and Glenlivet became well-known in foreign markets: in 1871, the Elgin Courant reported that it was sold all over the UK, and in North and South America, Europe, India and Egypt. But the main reason for the success of Glenlivet was the growth of blended Scotch whisky.

Brandy, a popular tipple among the rich and middle-classes in Britain, became increasingly scarce in the 1870s as the phylloxera epidemic destroyed vineyards across Europe.

Scotch whisky blenders sought to create a spirit that would appeal to those who had acquired a taste for ‘b and s’ – brandy and soda - and the Smiths adapted the traditional Glenlivet style to meet their needs.

Accessing supplies of coal through Ballindalloch Station – opened on the new Strathspey Railway in 1864 - they began to produce a less highly-peated whisky with a rich, fat character and a pronounced ‘pineapple’ flavour, which suited the blender’s requirements for a distinctive flavour component to mix with neutral grain spirits in their blended Scotches.

This evolving Glenlivet ‘style’ was consciously imitated by the new wave of distilleries opened in Strathspey during the boom years of the late 19th century. They took to advertising their whiskies as ‘Glenlivet’, and described their locations as being in the Glenlivet district.

The practice was so common that the Cardow Distillery boasted in 1894 to be the only distillery in the area "which has never found it necessary to affix the word Glenlivet to the original name”!

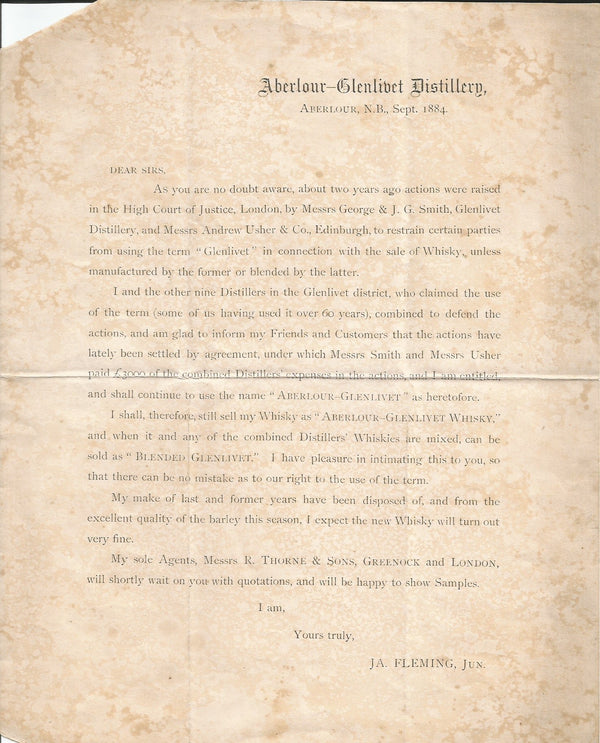

George’s son, John Gordon Smith, registered Glenlivet as a trademark in the 1870s, but he and his successors were unable to prevent other distillers and blenders from using the name: they claimed, with justification, that the name had become commonly used for whisky made in Strathspey and not just in the glen itself.

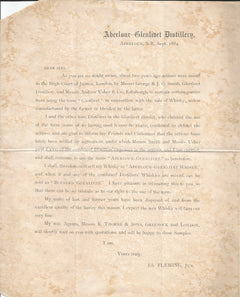

JA Fleming Jnr’s letter to his customers, 1884, explaining that he will continue to sell his whisky as Aberlour-Glenlivet.

He took legal action in the 1880s, supported by his agents Andrew Usher & Co, but failed to win sole rights to use the name: it didn’t help their case that the agent had named its flagship brand ‘Usher’s Old Vatted Glenlivet’, even though it was a blended Scotch containing and contained only a very small proportion of whisky from Minmore!

Eventually, the two sides settled their differences out of court. The definite article was added to the distillery’s name and the brand which the trade had hitherto referred to as ‘Smith’s Glenlivet’ became The Glenlivet.

Those distillers from other parts of the country who had advertised their whiskies as ‘Glenlivets’ continued to do so, eventually in hyphenated form (Macallan-Glenlivet, Cragganmore-Glenlivet etc.) and new entrants were admitted to the ‘club’ for a fee – in 1890, for example, Mackenzie & Co. paid £600 for the right to append “-Glenlivet” to name of their Dailuaine Distillery.

A “Macallan-Glenlivet” bottle.

This practice of using ‘-Glenlivet’ in distillery and brand names became less common after the 1970s as single malt brands sought to establish their own distinct identities but persisted until the end of the 20th century.

Blenders, meanwhile, felt free to continue advertising their brands as ‘blended Glenlivets’ for decades after the legal settlement of 1884. And the licensed trade continued to classify single malts from the Strathspey area as ‘Glenlivets’ even after a new name, ‘Speyside’ was introduced as a substitute for the category in the 1890s.

Glenlivet’s fame was not only as the original home of a style of Scotch whisky. It was also the birthplace and training ground of some of the most influential personalities in the Scotch whisky trade.

The Grants of Glen Grant Distillery, for example, were raised at Shenval in the glen. John Grant was a well-known smuggler in the 1820s, who also dealt in George Smith’s ‘legal’ whisky – he remembered later that he had to pretend to customers that it was from an illicit still, to obtain a higher price! John and his brother James subsequently built the Glen Grant Distillery in Rothes, which was one of the largest and best-known in Victorian times.

Another family of Grants farmed at Blairfindy, next to Minmore. In 1865 they leased the farm and distillery at Rechlerich in Strathspey, initially sub-letting the distillery (known as Glenfarclas) to John Smith, the son of the former brewer at Auchorachan. The Grants took over the running of the distillery in 1869 and J&G Grant are one of the few old-established distillery firms in Scotland to remain in family hands.

John Smith moved on from Glenfarclas to open a new distillery at Cragganmore, near Ballindalloch in 1870. Smith had worked as a stillman at Minmore and had experience working at distilleries in the north and in the Lowlands. Under his direction, Cragganmore gained an enviable reputation among blenders and its reputation as a top ‘Speysider’ has endured - it was chosen as one of the original Classic Malts by Diageo in 1988. John was not the only member of his family to make his mark in the distillery industry. His uncle William Smith trained at Glen Grant and became the best-paid brewer (a position akin to a distillery manager today) in the country. In 1843 he bought the Lynn of Ruthrie Distillery and, renaming it Benrinnes, greatly extended the business.

Unfortunately, according to The National Guardian, Smith was not only full of energy and enterprise, but ‘impulsive and somewhat erratic’ and ‘in too much haste to be rich and great’. His business failed in 1864 and it fell to others to capitalise on his achievements.

John’s brother George Smith was a steadier businessman. As manager at Ord Distillery, he ‘widened out the channels by which it found its way into the hands of many of the best houses in the Trade’, before moving to the Parkmore Distillery in Dufftown.

Other Glenlivet men made their names further from the glen. For example, James Grant, the son of the distillery manager at Auchorachan, was a key figure in the history of Highland Park on Orkney. He became a partner in the business there in 1885 and became sole proprietor ten years later. He is generally credited with laying the foundations for the success of a whisky known for its rich, fruity and subtly-peated flavour – a throwback, perhaps, to the old Glenlivet style.

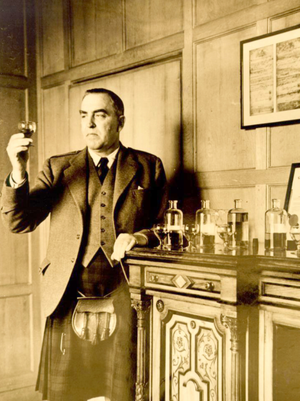

Jimmy Barclay (1885-1963)

“One of the greatest whisky entrepreneurs ever to graduate into the respectable era from the bootlegging days.” Image courtesy of Chivas Brothers Archive.

The whisky broker Jimmy Barclay was also raised in the glen, and he began his working life as an office boy at Benrinnes. Barclay became one of the great whisky buccaneers, a wheeler-dealer who dealt in companies as well as parcels of whiskies. At various times in his eventful life, he owned the Ballantine’s brand and Bladnoch Distillery, and he was a director of Hiram Walker’s Scottish subsidiary and of Chivas Brothers. Having made contacts with various American importers during Prohibition, he became the business adviser and agent in Scotland for Sam Bronfman of Seagram.

Barclay helped the Canadian tycoon acquire Chivas Brothers in 1949 and Strathisla Distillery a year later. For much of the 1950s, Chivas Regal was bottled exclusively at Barclay’s bottling hall in Glasgow.

Finally, there were George Smith’s descendants at Minmore. His son John Gordon Smith was followed by George’s grandson, George Smith Grant. As President of the North of Scotland Malt Distillers’ Association, the latter led the malt whisky distillers in their unsuccessful fight against the big blenders in 1909, in the investigation conducted by the Royal Commission on Whiskey and Other Potable Spirits to establish a definition for Scotch whisky.

Bill Smith Grant (1896-1975)

Image courtesy of Chivas Brothers Archive.

And the founder’s great-grandson Bill Smith Grant led the drive to re-establish the market for single malts in the USA, after Prohibition ended in 1933.

He worked tirelessly to establish The Glenlivet there during the 1940s and 1950s, despite shortages of stock in the aftermath of the Second World War, and The Glenlivet became America’s top-selling single malt.

The distilling industry became even more important to the glen in the early 20th century, as jobs in agriculture dwindled and the population fell to around 1,000 people.

The Glenlivet employed around 50 men directly, but many more on ancillary work. It also provided a social hub for the glen, in the workers’ village that grew up around the distillery and in neighbouring Bridgend of Glenlivet.

The distillers helped pay for the upkeep of the road to Ballindalloch, a vital link to the railway and the outside world. They supported the local school and church and made distillery warehouses available for local entertainments. Employees were encouraged to take part in sports and in the 1920s Bill Smith Grant laid out a 9-hole golf course on the banks of the Livet. The whisky business was at the heart of the social as well as the economic life of the community.

The Glenlivet’s monopoly of whisky-making in the glen ended in 1966 when Invergordon Distillers built a new distillery at Tamnavulin. It was closed in 1995, two years after the parent company was acquired by Whyte & Mackay but reopened in 2007 and employs a full-time staff of twelve.

Chivas Brothers brought distilling back to the Braes in 1973, when they opened the Braes of Glenlivet Distillery at Chapeltown. It was one of the first fully-automated distilleries in the country and is run by a core team of just four operators. Its name was changed to Braeval some years after parent company Seagram acquired The Glenlivet Distillery in 1978, and Braeval was closed from 2002-08 after the acquisition of Chivas Brothers by Pernod Ricard. Its greatest claim to fame, however, is probably that it was built 365m above sea level and competes with Dalwhinnie for the title of the highest distillery in Scotland.

Today, the population of Glenlivet has shrunk to around 200 people. But Glenlivet’s three distilleries provide jobs for many locals and for the inhabitants of Tomintoul and other small communities nearby. Glenlivet remains an important centre of industry and employment in Banffshire and an increasingly popular tourist destination. And its fame continues to spread across the world, wherever Scotch whisky is enjoyed and its stories are told.